Introduction and Key Concepts (Hexagonal Architecture with Spring Boot — Part 1)

Introduction to Hexagonal Architecture and Key Concepts

Using Hexagonal Architecture can vastly improve your code, but it is seldom well explained and rarely demonstrated.

This is the first article of a 4 5 part series explaining Hexagonal Architecture and how to implement such an architecture using Spring Boot and TDD.

Part 1 - Introduction to Hexagonal Architecture and Key Concepts

Part 2 - Coding demo project and implementation of the API adaptor

Part 3 - Implementation of Domain Services

Part 4 - Implementation of MongoDB repository adaptor

Part 5 - Implementation of REST adaptor to an external data source

Some History

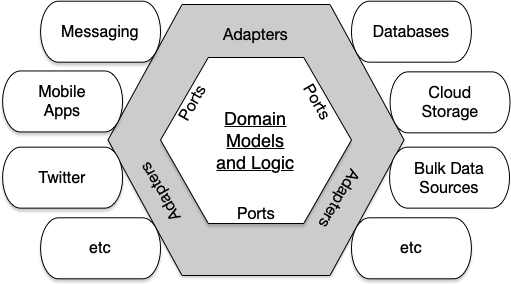

The Hexagonal Architecture was proposed by Alistair Cockburn in 2005 as an architecture for modularising applications. In the core of the architecture are the domain models and logic. This core is separated from external systems through a layer of Ports (interfaces) and Adapters (implementations), and the hexagonal architecture is sometimes known as the Ports and Adapters Architecture.

External systems include user interfaces, data repositories, storage systems, messaging systems, and other applications, as depicted below.

What’s Often Missing?

Most subsequent interpretations of the hexagonal architecture are, in my opinion, missing a few key points.

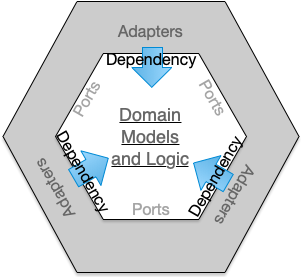

Uni-directonal, Acyclic Dependencies

The first essential trait of this architecture is that the code dependencies are always unidirectional and pointing inwards.

The implication is that the core, comprising the domain models and logic, is independent of the external systems except through the ports or interfaces. This applies regardless of whether the core is being called by, say, the REST controller, or if the core is calling, say, a database system for persisting the entities. Put differently, the direction of the dependency need not be the same as the direction of invocation.

Optionality

An implicit trait of hexagonal architectures is the optionality it enables for external technologies and systems.

This is especially important for cloud computing which presents us with not only a plethora of choices. You could choose today based on the current understanding of attributes like pricing, capabilities (e.g. max capacity, responsiveness, consistency characteristics, etc).

Take data persistence technologies, for instance. Today, we’re spoilt for choice not just in the wide varieties of SQL and NoSQL databases, we can also use cloud provider specific data storage (e.g. S3, DynamoDB, Cloud BigData, Cloud FireStore, Cloud Spanner, CosmosDB, and on and on).

The same applies for data and services providers. For example, if your system requires currency exchange rates updates, there are multiple sources to choose from.

And the best choices might change due to new product and updates, scale and volume, changes in requirements and your understanding of them, the project budget, just to name a few. The modularisation of adapter code in hexagonal architecture simplifies the migration between these technologies and providers.

Ports and adapters not only simplifies the selection and migration of external systems, designed correctly, the adaptor libraries can also be changed with less effort. Take database access for example. We could change the adapters between JPA, MongoTemplate, JOOQ , MyBatis, etc. For REST API adapters, we can write them in either annotation or functional styles.

Bounded Context and Microservices

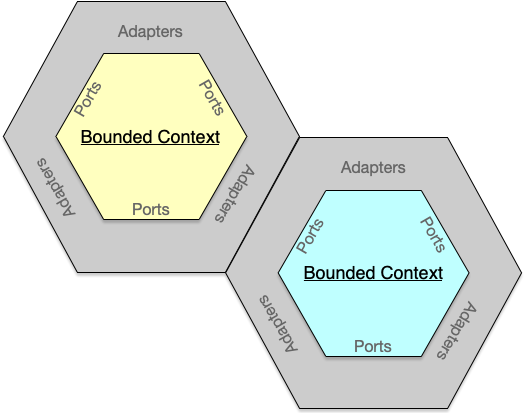

The third observation is many concepts in DDD (“Domain Driven Design”, proposed by Eric Evans in his 2003 book) maps well into hexagonal architecture. A large application can be decomposed through DDD into Bounded Contexts each of which can be implemented independently.

Communications between these bounded contexts are through ports and adapters, and the mechanism implemented using REST APIs, event buses, or similar inter-systems protocols. This fits neatly into Microservices design and implementation.

(I speculate that the hexagon shape that lends its name and form was chosen due to its ability to tesselate, illustrating a module’s ability to fit neatly together with other modules.)

Testability

The last benefit needs a bit more explanation. Two of the biggest problems in doing TDD (“Test Driven Development”) or testing in general are what to use a mock (or, more generally, test double), and how to write robust tests that don’t break every time you try to change the code.

Firstly, the separation of the core and the adapters through ports and interface contracts is a natural demarcation of test unit boundaries. In a Unit Test (but not necessarily in an Integration Test), you should use a test double whenever you cross between the core and the adaptors. And this should always be represented by a well-defined port with clear interface contract.

Secondly, we can push the data and states into the adaptors and make the core purely functional. Doing so renders the domain models and logic more testable and enables really fast and robust tests for them. This might not be as intuitive and is best elaborated in the coding below.