Writing Better Code with Reactor 3 - Part 1

Basic Concepts, Interfaces, Components

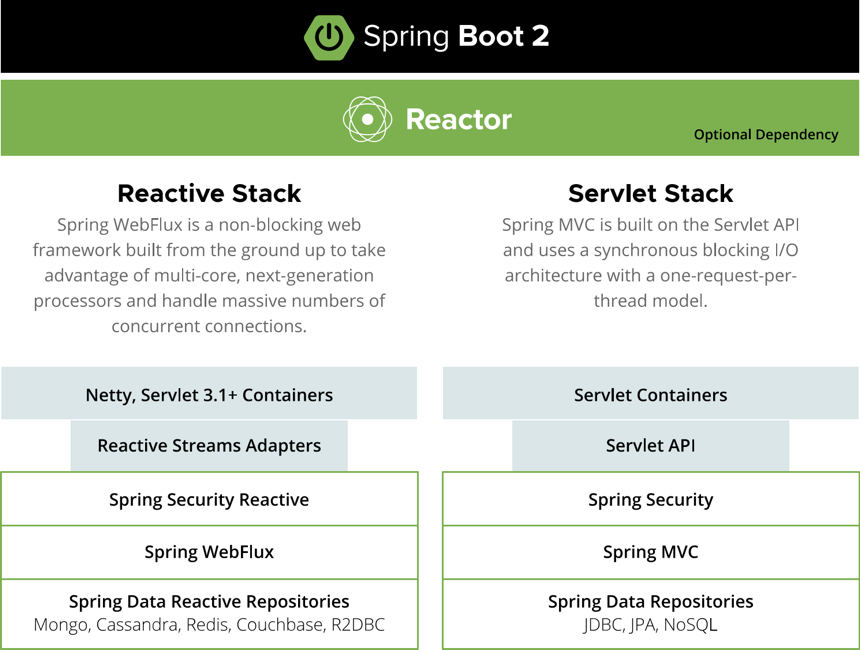

Reactor 3, or more generally, Reactive programming is one of the key changes introduced in Spring Framework 5 and Spring Boot 2. This reactive capability is built upon Project Reactor, which is a Java 8 implementation of the Reactive Streams specification.

So what are reactive streams and why do we need reactive programming?

Reactive streams is designed for asynchronous processing of “live” data streams, which often have data volumes that cannot be predetermined. A useful analogy is that of an assembly line that moves items from one end to the other, processing them along the conveyor belt. This is a common pattern especially for large scalable application services.

The reactive streams specify a non-blocking, event driven programming paradigm, with a back-pressure mechanism for controlling data flow. This simplifies implementation of efficient, responsive, scalable, and resilient systems with decoupled components.

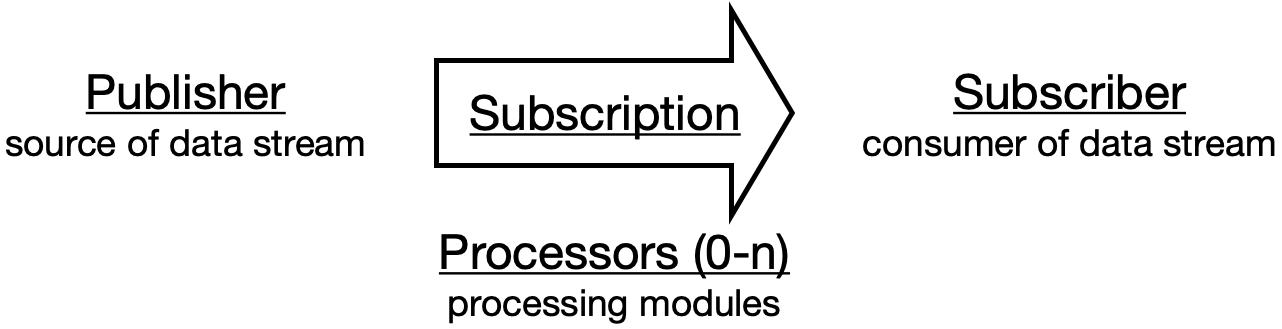

In Reactive Streams, a Publisher is a source of data, and a Subscriber is a consumer of the data. A subscription connects the Publisher and Subscriber, and there can also be any number of Processors, or processing modules along the subscription.

Let’s write some code to explore reactive programming with Reactor 3. We start with an empty Maven project.

In the pom.xml, we first set up the java version to Java 8 or higher.

This is because Maven defaults to Java 5 and Reactor requires at least Java 8.

Next, let’s specify the dependencies. while we can specify the versions individually, let’s use the dependency management provided by the bill of material for consistency.

The latest release BOM is the Dysprosium-SR7 version, which we’ll use.

We’ll include reactor-core for core reactor 3 functionality.

For testing, we’ll use junit-jupiter-api from JUnit5, and reactor-test.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<project xmlns="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0 http://maven.apache.org/xsd/maven-4.0.0.xsd">

<modelVersion>4.0.0</modelVersion>

<groupId>org.example</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-demo</artifactId>

<version>1.0-SNAPSHOT</version>

<properties>

<java.version>1.8</java.version>

<maven.compiler.source>${java.version}</maven.compiler.source>

<maven.compiler.target>${java.version}</maven.compiler.target>

</properties>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-core</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.junit.jupiter</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-jupiter-api</artifactId>

<version>5.6.2</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-test</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-bom</artifactId>

<version>Dysprosium-SR7</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

</project>

Next, let’s now create a test class to explore the core functionality of Reactor 3.

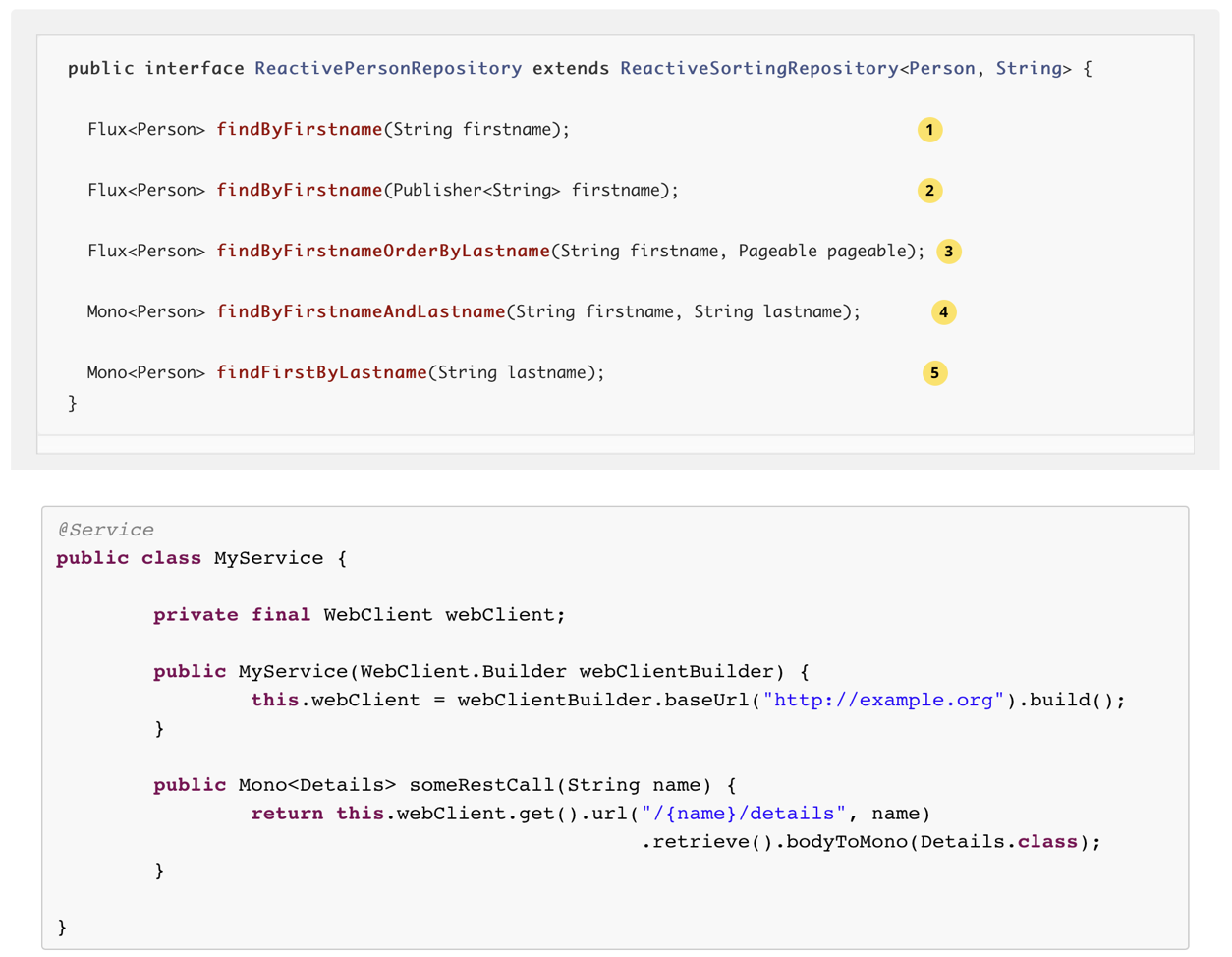

The primary Publisher in Reactor is the Flux, which represents an asynchronous stream of zero to any number of data elements.

A Mono is a specialised, simplified version of Publisher that represents a stream of at most one data element.

In a Spring application, a data stream typically originates from some request or response. For instance, the Spring Data interfaces of R2DBC and the reactive NoSQL databases, and the Web client interfaces return Flux and Mono data streams.

For this demo, we’ll use the Mono and Flux factory methods for generating static data streams

The just() factory method generates a Mono or a Flux from the parameters. So Mono.just(1) generates a Mono of an Integer, value of 1.

We’ll add a log() for observing the Mono. Nothing happens unless we add a subscribe() to start the data stream.

Mono<Integer> mono = Mono.just(1);

mono.log()

.subscribe(); // 1

Gives:

[ INFO] (main) | onSubscribe([Synchronous Fuseable] Operators.ScalarSubscription) // 2

[ INFO] (main) | request(unbounded) // 3

[ INFO] (main) | onNext(1) // 4

[ INFO] (main) | onComplete() // 5

Let’s trace the sequence of events in the log.

- First, subscribe() is called on the publisher.

- The publisher in turn calls onSubscribe() on the Subscriber, sending it a Subscription parameter.

- The Subscriber then calls request() on the Subscription to start the data flow.

- Subscriber’s onNext() is called with each data element, and

- then onComplete() is called at the end of the data stream.

Remember that a Mono can only have at most 1 data element, so we cannot specify more data elements

Instead, we can use Flux.just(1, 2, 3) use generate an Integer Flux of 3 data elements, 1, 2, and 3.

Flux<Integer> flux = Flux.just(1, 2, 3);

flux.log()

.subscribe();

Gives:

[ INFO] (main) | onSubscribe([Synchronous Fuseable] FluxArray.ArraySubscription)

[ INFO] (main) | request(unbounded)

[ INFO] (main) | onNext(1)

[ INFO] (main) | onNext(2)

[ INFO] (main) | onNext(3)

[ INFO] (main) | onComplete()

Let’s subscribe to the flux and observe the event log. We’ll see the same sequence, with an onNext() with each of the data element, then onComplete() at the end.

Besides observing the events though log(), we can also intercept and process each event in the data stream.

We can intercept the onSubscribe event with doOnSubscribe(), and print it out or capture the subscription in a field for later.

We can intercept the request event with doOnRequest() and examine the request parameter.

Perhaps more useful, we can intercept the data elements with doOnNext(). Similarly we can capture cancel, error and completion events with doOnCancel(), doOnError() and doOnComplete()

flux.doOnSubscribe(s -> {

System.out.println("SUBSCRIBED - Subscription: " + s);

subscription = s;

})

.doOnRequest(n -> System.out.println("REQUESTED - request: " + n))

.doOnNext(item -> System.out.println("NEXT item: " + item))

.doOnError(e -> System.out.println("ERROR: " + e))

.doOnCancel(() -> System.out.println("CANCELLED"))

.doOnComplete(() -> System.out.println("COMPLETED"))

.subscribe();

We can also specify the behaviours in the subscriber instead of using these methods. The first optional parameter of subscribe() is the data element consumer. The next optional parameter of subscribe() is the error consumer. The third parameter of subscribe() is the onComplete() runnable, and the

The last optional parameter to subscribe is the onSubscribe() consumer. This option is seldom necessary and should be used with care. If I just move the onSubscribe() behaviour here, you’ll find that the data stream does not start. This is because the request() call is missing, and you are expected to call request on the subscription.

In the default scenario, request is called with Long.MAX_VALUE which indicates request for as many elements as there is in the Flux.

flux.subscribe(

// onNext

item -> System.out.println("NEXT item: " + item)

// onError

, e -> System.out.println("ERROR: " + e)

// onComplete

, () -> System.out.println("COMPLETED")

// onSubscribe

, s -> {

System.out.println("SUBSCRIBED - Subscription: " + s);

subscription = s;

s.request(Long.MAX_VALUE);

}

);

We can also apply back-pressure by indicating the maximum items the subscriber is prepared to accept next. Let’s say we only have capacity for processing the data elements one at a time, then the request would be for 1 element, and the next request is only called when capacity is freed up

flux.subscribe(

item -> {

// process

subscription.request(1);

}

// onError

, e -> {}

// onComplete

, () -> {}}

// onSubscribe

, s -> {

subscription = s;

s.request(1);

}

);

Besides integers, we can create Mono and Flux of other types. We can create publishers of Longs, Strings, Objects, Lists, Maps, even other Publishers.

Besides the just() factory method, we can also generate Flux from ranges and from iterables such as lists, from streams, and from arrays.

We can also generate an indefinite sequence of Long values (incrementally from 0) using the interval() method from Flux. We specify a Duration that’s the interval between each data element.

Flux<Integer> range = Flux.range(0, 3);

Flux<Integer> fromIterable = Flux.fromIterable(list);

Flux<Integer> fromStream = Flux.fromStream(list.stream());

Flux<Integer> fromArray = Flux.fromArray(array);

Flux<Long> flux = Flux.interval(Duration.ofMillis(200));

You can also watch a screencast of this tutorial.